Preface 2 Toys as Commerce, Childhood as Nation

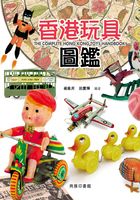

Wooden duck, 1941, South China Toys Factory Ltd., Hollywood Road, Hong Kong

Small, colourful and money-spinning, toys are emblematic of Hong Kong.

The vintage plastic ducks, winsome dolls and wobbly robots pictured in this publication represent a time when children around the world grew up with toys stamped ‘Made in Hong Kong’, and when the factories that made them were at the forefront of the city's industrial hyper-growth. Such toys are mascots for the ‘Hong Kong legend’, the rags-to-riches story in which a hotchpotch of post-war factories was transformed, by toil and tireless enterprise, into a global centre for the trade in toys and games.

Yet the history of Hong Kong toys is more far-reaching than the legend. Its roots may be traced back to the first local toy factories of the Thirties and, further still, to the 19th century ‘China Trade’ that rifled the ancient treasury of Chinese toys for ingenious games and novelties to be adapted for Western tastes. The industry's modern history has been equally expansive, first in forging new models of international brand licensing, then in relocating this system across the border to spearhead burgeoning growth in South China's manufactures. More recently, local toy making has branched out in unexpected directions to generate new educational and electronic games, radical ‘urban vinyl’figures and digital character animation. So it is a surprise that Hong Kong has no public museum dedicated to local toys. There is no museum of childhood either, or of play. No specialist toy design course survives in tertiary education, and no historian has explored the cultural reasons why this small region of China has been so phenomenally successful in toy production. In a city that has made more toys than any other, why do we neglect this heritage?

This question was a starting point for discussion when the Hong Kong Museum of History first invited myself, joined by the co-authors of this foreword – Anita Tse Muse, Fonny Lau Yuet Po and Rémi Leclerc –to prepare research on local toys. Might the answer be that toys are still regarded as trivial, if charming playthings –an ambivalence dramatized eighty years ago in Sun Yu's famous propaganda movie Toys? Is it possible that, even now, playing with toys is considered a waste of time –as in the stubborn Chinese aphorism: ‘diligence has its reward; play has no advantages’? Or are toys still viewed as frivolous imitations, as little copies of the grown-up world – and so overlooked as models of creative invention?

In the never-ending story of toys there are few beginnings but many zigzag journeys that transport us across centuries and continents. Some of the most ancient games and toys undoubtedly began in China, from the popular Han game of football to the Song tangram or Ming diabolo in its many guises. Their origins and circulation around the world are mysterious, for many ancient Chinese toys also appear in other early civilizations. For example, the bolanggu, a percussive toy with beaters attached to a drum also occurs in ancient Egypt. Clay whistles in the form of birds or animals appear in Han times, but also in the archaic Mayan civilization. The yo-yo, pull-along toys, the whipping top and hobby-horse also existed in Classical Greece, the Roman world and India.

Dolls, or at least figurines, are of course universal, although the oldest surviving figurines in China are fertility or grave goods rather than toys. Clay figures from Wuxi and Tianjin, together with delicate dough sculptures and string puppets are centuries old, although the cloth and opera puppets of Fujian came later: the name ‘budaixi’ suggests the Indian ‘putali’, a puppet theatre that may have arrived with the region's monsoon trade to the subcontinent during the early Ming. And the modern Chinese term for doll (洋娃娃) suggests a Western influence. Indeed, quantities of opera dolls and nodding head dolls were produced in the late Qing era for export to the West.

Some traditional-sounding toys and games, such as Chinese Chequers, turn out to be nothing of the kind:in this case the name was invented by an American company marketing the Stern-Halma, a board game developed in Germany as recently as 1892. Marketing can also reinvent tradition. For example, the lanterns and illuminated toys of Hong Kong's Mid-Autumn Festival are unusual since, in every other part of the Chinese world, they are associated with the Spring Festival. It appears that during the Seventies Hong Kong's Tourist Authority sought to counter the sharp fall in hotel occupancy after the summer season by encouraging touristic displays of lanterns during Mid-Autumn.

Since the origins of most of the world's classic toys are obscure it is more revealing to begin an account of toy design not with legendary accounts of their creation but rather with their slow, and often epic journeys of transformation.We begin with just one example: the dragonfly. The traditional Chinese bamboo dragonfly, spun by hand or by a string wound on a spindle, gyrates over the millennia and around the world to become the robotic flying dragonfly toy made in contemporary Hong Kong. The origins of the bamboo dragonfly are obscure, although scholars have speculated that the device is referred to in Chinese, or perhaps Greek texts from 400BC. Traded across the Silk Road, and perhaps further adapted in Hellenistic Syria, the Chinese toy appears in the West around 1500, pictured in a Madonna and Child by the Flemish painter Jan Prevoost, and held by a playful Christ child –here adapted to four rotors to symbolize the cross and, curiously, combined with a Chinese whistling top to represent the world.

Western adaptations of the bamboo dragonfly may have inspired Leonardo da Vinci's famous studies of flight, and certainly the Chinese toy fascinated European scientists of the late 18th century such as the engineer George Cayley, who first formulated the aeronautic principles of the helicopter. In the modern era, as bamboo was replaced by plastic, the helicopter rotor was re-adapted to Hong Kong flying toys. The catalogues of Ting Hsiung-chao's Kader Industrial Company from the early Sixties show a new Flying Wheel version of three rotors on a wheel, also marketed as a Flying Saucer. Around the same time an unknown Hong Kong manufacturer packaged a similar toy on a print of an RAF Rescue helicopter, the first to market the dragonfly as the Baby Copter. A decade later many local companies adapted the draw-string principle to power model helicopters, that would soon be further adapted to battery power and then radio-control. It was a short step to the beguiling ornithopter dragonfly, part of the Robosapien range of flying toys made in Hong Kong for the Canadian company WowWee Toys in 2007. The dragonfly characterizes the evolution of most modern toys that have been shaped by countless craftsmen, traders, manufacturers and entrepreneurs each in pursuit of market advantage.

Hong Kong's early industries, including the toy industry, were already well developed on the eve of the Japanese Occupation. Adjusted for post-war inflation, it would take almost two decades for the value of domestic exports tofully recover. More significantly for the story of toy manufacturing in the city, the earlier industrialization of Hong Kong included both Cantonese and Shanghainese toy factories from the Thirties. In 1936 for example, the Cantonese South China Toys Factory was established in Hollywood Road by Wong Pik-shen to produce a wide range of paper snakes and fans, dolls, tin toy trumpets, cars, planes, furniture and utensils, pull-along wooden aircraft, ships and ducks.In turn, these early factories drew on deep cultural and commercial roots in the old China Trade.

More than two centuries ago toys were already a notable feature of the China Trade. At a time when Western imports from China were fast expanding, from tea and silk to the tangram puzzle (which became compulsive pastime from America to Europe), the British sent a diplomatic mission to the Qing Court to negotiate greater advantages in trade. In 1792 John Barrow, secretary to this mission, described how “All kinds of toys for children, and other trinkets and trifles, are executed in a neater manner and for less money in China than in any other part of the world”. Ironically, among the Western gifts of “toys” presented to the Emperor Qian Long such as decorative automata by the English inventor James Cox, a number had been manufactured in China for, as Maxine Berg revealed, Cox's son had already discovered the cost of manufacturing in Guangzhou to be a third of the price paid in London. Fifty years later, William Hunter's account of Fan Kwae at Canton recalled the “prodigious” number of “cargo boats, sampans, ferry boats plying to and from Honam with quantities of vendors of every description of food, of clothes and of toys”, recalling a grisly souvenir of a miniature skeleton which popped up from its little wooden casket. Although skeleton puppets have a long ancestry in China and are depicted in paintings of the Song era (most famously, and disturbingly, in Li Song's Skeleton's Magic Puppet, trade items were made for export. This novelty was to survive into the twentieth century as a plastic toy, manufactured in Hong Kong in various forms as a piggy bank or Halloween toy and, after more than two centuries, is still produced in South China.

Large quantities of Chinese toys found their way onto cargo ships from the late eighteenth century, bound for Europe and America, increasingly tailored to market demand. Travelling hawkers would also carry their wares overseas to become the first international salesmen for Chinese export toys. Some of the products sold by peddlers, story-tellers and festival entertainers would survive into the modern era. The traditional peephole amusement for example, a favoured subject for China Trade painters, would be transformed in material, form, scale and meaning to become the optical peephole plastic toy produced in Hong Kong during the 60's, moulded in the shape of radio or television sets,and so retaining a distant connection with oral story-telling.

Following the expansion of trade routes from the port of Hong Kong, toy hawkers journeyed to overseas Chinese communities in Asia and, by the 1880s, were already a familiar sight in cities as distant as Melbourne and San Francisco. Contemporary Western illustrations and photographs show toy hawkers supplied with both traditional wares, such as paper windmills, kites and wooden snakes, as well as items adapted to Western tastes, such as miniature parasols (later marketed as a cocktail decoration), cloth dolls and paper festival lanterns. The latter would be adroitly re-purposed in Hong Kong factories since the Thirties overprinted with ‘Merry Christmas’.

China Trade toys, amusements, souvenirs, games, novelties and gifts were manufactured for export through an extensive system of serial production that involved family factories spreading from Guangzhou to many towns of the Pearl River delta, including Hong Kong. The range of materials quickly expanded beyond paper and cloth to include wood, glass and more expensive ivory, tortoiseshell and silver toys.

At the turn of the 20th century exquisite Chinese games and novelties were already being retailed by Hong Kong's new ‘Australian’ department stores such as Sincere, founded in 1900 and Wing On, founded in 1907, and by long-established ivory shops, silversmiths and emporia of Wellington Street and Queens Road such as Kruse & Company.Miniature toy ceramic tea sets, ivory tops, cup-and-ball games, puzzle boxes and novelties, such as the tumbling Chinese acrobat, were retailed by shops such as Lee Ching and Cumwo, and represented an opulent extreme to the modest wares of the travelling hawker.

Manufactured toys and games are a recent phenomenon. Until the later nineteenth-century most children fashioned their own toys, as most children outside the affluent world still do today, and made up their own games. In the imagery of the traditional Chinese ‘hundred children’ motif many of the élite little boys seen frolicking in gardens are depicted with make-believe swords, bows, flags and streamers improvised from sticks or scraps of cloth, as for hide-and-seek, or they play with crickets, toads or lotus leaves.

In modern Hong Kong by contrast it is common to hear parents complain at the superabundance of modern toys by recalling that “when we were young we had to make our own toys” … the same sentiment expressed by their own parents in the early Eighties. Perhaps a contrast between past and present remains an enduring topos of the city's ‘rags-to-riches’ legend for both hand crafted and semi-manufactured toys had long been offered by hawkers in Hong Kong around festival time, and at local amusement parks like Liyuen, or by snack shops. From the Fifties, snack shops hired out comics and retailed a range toys in cellophane bags stapled to printed cards –cards sometimes used as‘lucky draw’ tokens, or for gambling. Such semi-manufactured toys ranged from shuttlecocks to paper cut-out masks, paper dolls with a range of clothing that could be coloured, and many small novelties and board games like Jungle imported from the Mainland. By the early Sixties, over-runs of locally manufactured toys were also available in Hong Kong street stalls, as shown in a 1964 photograph by Ho Fan depicting a boy choosing a plastic doll. At this time some companies also produced toys for the local market, such as the now iconic ‘Watermelon wave’ football, with a light bounce suitable for the confined urban spaces, designed by Dr Chiang Chen's plastics company Chen Hsong.Memories of childhood are therefore apt to be influenced by what we believe childhood ought to be.

For ‘childhood’ too is a surprisingly recent concept. As Andrew Jones has shown, modern Chinese intellectuals of the May 4th Movement such as Zhou Zuoren claimed there was no concept of ‘childhood’ in the entire Confucian tradition, which had dismissed children as simply ‘little adults’ whose moral education would be harmed by playing with toys. Some thirty years later the French historian Phillipe Ariès’ study Centuries of Childhood, would argue that until the Seventeenth or Eighteenth centuries Western culture also had no ‘idea’ of childhood and viewed children as ‘little adults’.

Later scholars such as Anne Wicks have shown these claims to be over-simplified: every culture has its own ideas about childhood and play, even if they differ from our own. Literati artists in the Song era delighted in painting children in domestic scenes, for example playing with intricate toys or excitedly clustered around toy peddlers or puppet shows.In the decorative arts, the ‘hundred children’ motif remained popular for centuries, along with images of plump toddlers in Chinese New Year folk prints. Such images depict many children's toys, from kites and spinning tops, windmills, drums and string puppets, riding in carts or on hobby-horses. All carried symbolic meanings, yet the sheer number of children featured in the literature and art, prints and books of the Song demonstrates that in earlier times there existed a lively interest in the world of the child, their games and toys.

Nevertheless, it is clear that the philosophical, cultural, political and commercial concern with childhood, play and toys emerged relatively late in history. The notion that childhood shaped adults, rather than the other way around, was first popularized by European philosophers and poets of the Romantic era, such as Wordsworth for whom: “The Child is father of the Man”. Later, these ideas would be given practical expression in the work of educational and social reformers – as well by industry, for childhood soon emerged as a very lucrative market.

In China by contrast, children moved centre-stage at the turn of the twentieth century as national movements of modernization and cultural renewal struggled to forge a new society in the wake of colonial onslaught and revolution–a politicization of childhood that would be equally acute in Japan, Russia and Germany, and perhaps as insidious in corporate America. In 1929, the leading Chinese intellectual Hu Shi wrote (in Hsiung Ping Chen's translation) “To understand the degree to which a particular culture is civilized, we must appraise …how it handles its children.”

However, when Chinese reformers sought toys for the domestic kindergarten movement they relied on Japanese toy imports, as well as Japanese versions of Rousseau and Fröbel. Translated into Chinese in 1903, the Japanese Seki Shinzo's 1879 Pictorial Explanations of Educational Toys inspired both intellectuals and industrialists to develop home-grown educational toys. In 1911 Jiang Junyan opened the Great China Factory to manufacture celluloid toys and games. This would be the first of dozens of toy factories that would flourish in the Twenties and Thirties in Shanghai and other major cities, including Hong Kong, to manufacture wood, tin and celluloid soldiers, tanks and battleships –and a few Fröbelian play blocks. Susan Fernsebner has shown how businesses used foreign toy makers as role models to improve their own products, while at the same time capitalizing on political boycotts against Japan and new political ideals to promote domestic sales. For the Republic supported the toy industry not only to stem the tide of foreign imports but in the belief that authentically ‘Made in China’ toys would mould children into modern identities as engineers, soldiers, mothers and consumers, and so strengthen the economy of the new society.

Zhou Zuoren's sweeping claim that “China has not yet discovered childhood”, and the idealism with which he sought to expose what the historian Hung Chang-tai described as the “grievances” of Chinese children were both loyally supported by his brother, the writer Lu Xun. With its poignant last line, ‘Save the children!’ Lu Xun's landmark vernacular story from 1918, A Madmans's Diary, had already positioned the child on the front line of the struggle to escape tradition. In his short story of 1925, The Kite he looked back on a childhood incident in which he smashed his little bothers’ kite, confessing that his punishment only came twenty years later when: “I came across a foreign book about children. I realized only then that playing is the most normal behavior for children, and that toys are their angels.”

Yet Lu Xun was ambivalent about the extent to which China could escape the past, and about the instrumental politicization and commercialization of the child in the new Republic. The campaign to promote Chinese toys as ‘National Products’ led to the establishment of a ‘Year of the Child’ in 1933. Karl Gerth records that at one ‘Childrens’ Day’ rally, Zhou Zuoren's wife organized a display of educational toys and urged children to “keep to their hearts” Chinese made toys. However these campaigns had little economic effect. During the boycotts of 1934-35 imports of Japanese toys to China actually rose 70%. The embarrassment of finding that children's toys were all ‘Made in Japan’ would be the subject of several stories published anonymously in Shun Pao: Qingnong's Playthings in 1933 and Mi Zizhang's Toys in 1934.Mi (a pseudonym of Lu Xun) dryly observed that even in the ‘Year of the Child’ balloons with messages such as‘Completely National Goods’ (a message that grew ever larger as the toy was puffed up) were fake: the toys were just Japanese imports.

A wealth of new children's literature devoted to toys promoting the political, cultural and economic ambitions of the Nationalist government emerged in the Twenties and Thirties. In 1920 Guo Yiquan's How to Make Toys encouraged parents to fashion playthings with traditional materials, but such amateurism was quickly overtaken by publications promoting industrial-scale toy production. In the same year the Commercial Press lunched Children's World and a year later Chunghwa published Little Friend, together with children's section of the Beijing Morning Post –although as Laura Pozzi has shown most newspapers continued to carry prominent advertisements for imported toys. Pamphlets like Zhou Jishi's 1935 My Toys and the following year Xu Jingyan's Fun Toys encouraged parent to buy Chinese-made toys for their children, and in 1938 cartoonist Liao Bingxiong “Chinese Children Rise Up!” presented the child on the front line of defending the country.

The Commercial Press even ventured into educational toy manufacturing. As historian Andrew Jones relates, these toys were self-consciously advertised as ‘national products’ in the Press’ own publications like the 1932 Renaissance Mandarin Textbook “Toys are good, lots of toys / My toys are Chinese goods / Little whistle, made of bamboo / Spotted horse, made of wood / Little white rabbit, made of clay / Little mouse, made of paper / I am Chinese, I buy Chinese goods.”

The following year the now classic Chinese movie Toys by Sun Yu played on all the ambivalences of toy production in the tense political atmosphere of the impending war with Japan. Sun Yu's film follows the story of a village designer(played by Ruan Lingyu) of innovative craft toys who is lured to Shanghai in order to learn from the ‘Great China Toy Factory’ only to end up destitute, railing at a crowd of onlookers that China had only toy soldiers and toy planes to defend itself from the enemy.

This intersection between politics and toy manufacturing would re-echo in post-war Hong Kong toy manufacturing.L.T. Lam, now famous as ‘father of the yellow duck’, recently described a childhood memory in which his mother explained that Japan became rich by “selling toys to get money for guns and bullets”. In a patriotic flourish, he maintained that his motivation to manufacture toys was to compete against imports from ‘those vile Japanese who had made a great deal of money by exploiting us’, since “we should not pay money to our national enemy, should we?”

Matthew Turner

Acknowledgement: Parts of the above text were written as part of a research project commissioned in 2015 by the Hong Kong Museum of History, and are reproduced here with kind permission.