PROLOGUE

BELIEVING IN MY IDEA

WHEN NO ONE ELSE DID

“You have to go through a lot of nightmares before you realize your dream.”

After six-and-a-half grueling laps of jumping barriers and water pits, it was down to the last lap. I was at the Pacific-10 Track & Field Championships, representing the University of Southern California in the steeplechase. It was my last collegiate race and I had been training like a seasoned Olympian in hopes of breaking the university’s long-standing record. I was on the final lap of the race — a lap away from experiencing another nightmare.

I stepped onto the final barrier. My foot slipped on its slick surface. Tumbling into the water, I hit my shin. I was down. The filthy puddle splashed into my mouth, making me gag as I tried to prop myself up. I watched my competitors pass me while memories of falling during my final high school race loomed. Same results, last place, I thought.

My parents walked away in disappointment. My coach reacted the same way. All our hard work and scrupulous effort had been futile. I knew it: I was a loser. My defeat seemed to begin the day I finished dead last in that race, one day after I graduated from college, and it didn’t cease in the years that followed.

Initially, after graduating from USC with a degree in economics, I tried to stay in Southern California. I filled out job applications, sent resumes, took aptitude tests, and knocked on doors looking for an entry-level position related to my field — from accounting to investment banking. With every interview, I was confident I had the right skill set, education, work ethic, and personality for the job. Yet despite an encouraging interview, the employer always left me with notorious words: “We went with someone else.”

For months, I landed one interview after another, but never earned an offer. Each time I followed up, it was the same story — I didn’t have enough experience for the entry-level position. “I hope you’re not coming back to live with us,” my dad emphasized. My parents grew concerned and frustrated. Still, they did everything possible to provide me with support: enrolling me in career counseling, professional interview courses, and resume-building sessions.

My dad had taught me something that always resonated with me: Be aggressive and persistent. Once, when I was in college, he dropped me off at a buffet restaurant in the hope I would find a summer job as a dishwasher. I had worked at another outlet in the restaurant chain and was wearing the company uniform and name tag. “You’ve got to work,” my dad said as I left the passenger seat. I walked into the restaurant looking for the manager, who was confused when he saw me in full uniform, as though I had stolen it from another employee.

“I’m looking for a job here, since I worked at another location,” I explained.

“I see you have the uniform already,” the manager said.

“Yes, just register me on the payroll and I’m ready to start.”

“Do you speak Spanish?”

“Not really.”

“We’re looking for someone who speaks Spanish,” he reasoned. Even in a basic, entry-level position, I still couldn’t land a job.

After three months and failing a dozen interviews in Southern California, I was running out of money. My mom suggested I return home to the San Francisco Bay Area, where she thought I might catch a break finding a job. Maybe Los Angeles is too competitive, I thought. But when I moved back home, my humiliation deepened. I was ashamed to use my parents as a safety net. I knew I was a capable college graduate, but my pride was deteriorating and my self-esteem started to fade.

I continued my job search in the Bay Area, but had no more luck than in Southern California. I would make presentations for potential employers, receive positive feedback after my interviews, and return home bragging to my parents. But as I waited for potential employers to reply, there was never an offer. After forty-plus consecutive failed interviews, I knew something in my life had to change.

My parents didn’t help the situation; in fact, they exacerbated it. Both my parents had lived the American Dream, coming from nothing and working their way to success. My mom, a New Jersey native, had been working since she was a teenager. My dad immigrated to the United States from Afghanistan on his own when he was only sixteen, making ends meet to pay for his education before becoming a successful entrepreneur. I had always maintained a close relationship with my parents, which might have been the reason for their pressure and disappointment. The more failure I experienced, the more their support for me diminished. “You’re a loser, a disgrace to USC,” my mom would say, guilting me over the free room and board at their house. My dad would throw me out of bed at 5:00 a.m. to do chores and look for jobs. They couldn’t understand why I had not found one after going on several third-round interviews and being a runner-up. As a result, our house became a war zone.

Growing desperate, I was eager to try a new career path. So I decided to channel my athletic background and love of sports into coaching. I spent two months sending over 18,000 e-mails to every collegiate coach in the country, only to earn an offer to volunteer for the women’s cross-country team at Northwestern University. My parents were happy to see me off, and I moved to Chicago — supplementing the coaching position with odd jobs, from painting my landlord’s houses to part-time accounting.

After the season at Northwestern, I volunteered for a position coaching with the University of Virginia’s football team. When that position also failed to become paid, I knew I had to move on again. I accepted another volunteer coaching position with the track team at the University of Georgia, but soon realized that as a volunteer coach, I was swallowed up in another vicious cycle of failure: The positions never led to paid full-time. Before moving to Georgia to continue the cycle, I decided to visit Florida during spring break with the little money I had saved from working in Virginia at Bed Bath & Beyond. And that’s really where it all began.

I was riding a train from Orlando to West Palm Beach, Florida, touring aimlessly around the state. Beside me on the two-hour train ride sat a gentleman who asked, “What do you do for a living?” At the time, straddling volunteer coaching and odd jobs as I was, I couldn’t give him a straight answer.

“Well, right now, I’m trying to work my way up to a full-time coaching position,” I told him. He was impressed with my perseverance and dedication, he told me after I shared how the past three years of my life had been such a struggle.

“I like your character. You have a lot of potential,” he said. “Contact me if you’re looking to work as a regional manager for CVS Pharmacies.” A job offer? A real job offer? I wasn’t even wearing a suit! I hadn’t even been called for an interview! He never even saw my resume! I couldn’t believe it. The job he offered wasn’t coaching, and working as a CVS manager wasn’t something I ever thought I’d do, but he handed me his business card as we both got off the train. He went his way; I went mine.

Staring at his card, I reflected on his proposition and my current situation, lost in my own career path — or lack thereof. I thought of how different my life would be if I moved to yet another state. I thought of the different industries and contrasting cultures throughout the U.S., and my curiosity was piqued. I had spent the first three years of college at the University of Oregon, before transferring to USC. When I lived in Oregon, I thought of the loggers. When I lived in Chicago, I always thought of the trains. Living in Virginia made me think of the state’s rich history. There in Florida, I couldn’t stop thinking of the amusement parks. There was so much to the country that I hadn’t yet seen, and as I tried to find a career path that was the best match for my own personality and interests, there was still so much left to discover.

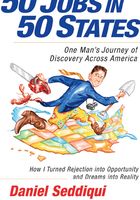

My mind began to race, and I had an epiphany. I thought of working a stereotypical job in each state. I wanted to live the map. As a child, I was always intrigued by maps, studying them for hours at a time, envisioning how people lived across America or how different I would be if I grew up in a different environment. When it occurred to me to work fifty jobs in fifty states, it was as though I had realized a dream I never knew I had — like waking up from a lifetime of pursuing the wrong path. Despite the struggle I had experienced since college, I had found ways to fulfill my curiosity about different cultures and environments — but this idea would also give me a chance to experience jobs. As my spirits lifted in excitement, I went to Georgia after spring break, as planned. In the weeks that remained until my coaching position started, I sold kitchens at Home Depot and worked vigorously on a plan to pursue fifty jobs.

I had no clue how to go about it, so I started by composing a resume of the most quintessential American jobs — one for each state, representing the culture and economy of each. It came to me like a natural instinct — without hesitation or second thoughts. Before my coaching position in Georgia even began, I knew I needed to return to California to make my vision a reality. With my college network in Southern California and my family in Northern California, I figured that if I returned to the state, I would have better luck constructing a plan, recruiting sponsors, and even selling my idea as a television show.

I left Georgia after one month. That also meant leaving Sasha. We had met in Atlanta, and she had become a close friend and ally. When I felt most alone and defeated, Sasha would encourage me to believe in myself. Though she was temperamental, I found her to be fun and kindhearted. As our friendship evolved, my feelings for her evolved too. I felt like nobody else existed when we hung out, and I believed we were meant to be together, but despite her incessant flirting, she claimed she did not want to be with me. Still, she left me with a glimmer of hope: “I would be lying if I said there’s no potential between us,” she told me before I left Georgia.

Sasha was the first girl to tell me she cared about me, and she encouraged me to fulfill the vision of my project. After so much adversity, I needed just one person in the world to believe in me, to make me feel that maybe, if I went for it, I could make the fifty jobs happen. Sasha was that person, that sole advocate, and in turn, I made a promise to her that I would return to Georgia a success.

I went back to Southern California, rented a car, and lived out of it until I could make ends meet. I was not welcomed back home by my parents. I shared my idea with them, but they immediately wrote it off as a waste of time, destined to fail. Though I now had a goal — my mission to work fifty jobs — I still needed to earn money until the dream became a reality. I was back to interviewing for office jobs — and back to being rejected.

After three jobless years, I found myself back to the same nightmare I had lived the last time I was in California. I bought a new suit from Macy’s to wear on a job interview that “I had no real intention of keeping unless I actually got the job,” I told myself. The interview was canceled as I was driving to it. That very night, I went back to Macy’s to return the doomed suit. Walking back to my rental car, my three years of failure followed me like a dark cloud. I was overcome with defeat. I had no alternatives. I had no place to go, nobody to turn to. I had been sleeping in that rental car for weeks. I was hungry. I was thirsty. I was at an ultimate low, as low as a sober person could go. I didn’t care about myself anymore. All I had was an idea.

I got in the rental car and pulled out of the Macy’s parking lot, driving aimlessly on the freeway. Within moments, a semitruck violently cut me off, and the car swerved into a curb, nearly hitting a wall. My heart was throbbing. I was scared and felt delusional from lack of food and exhaustion. I got off the highway to park and catch my breath, but I completely broke down. Slumped over the steering wheel, I sobbed until I was out of breath. My face shivered. I had never felt such a low before or such worthlessness. I picked up the phone and called my house. My dad answered, wondering why I was crying. I explained that I almost got into a car accident.

“You don’t have insurance. What are you doing? How come you never listen to us? Why can’t you keep a stable life?” he scolded me. Fortunately, my mom was more sympathetic and urged me to come home and rejuvenate myself. As I returned home to the fortress of failure, I resolved that I was tired of waiting for employers to determine my destiny. I was tired of waiting for opportunities to come my way. Throughout my life, I had been given advice, strategies, tools for success, but in the end, no matter how much coaching, I was the one who had to run the race. And I was the only one who could control the outcome.

Without a penny to my name, I had nothing to lose. I had planned on turning my idea into a television show, but regardless, whether I should pursue my vision of Living the Map was no longer a question. There was no reason not to.

As soon as I made up my mind to make it happen, nothing was going to stop me. My parents weren’t interested and didn’t want to hear about it, so I discreetly worked on my project, developing the plan and building a web site. My uncle told me, “If the why is strong enough, the how becomes easy,” and though lining up jobs was anything but easy, committing myself to making it work was.

I sat in my childhood bedroom making phone calls to employers across the country for sixteen hours of each summer day. I kept a log of every person I called, tracking responses. Some laughed at me, some hung up on me, and others made no attempt to hide their skepticism. I had heard “no” before and it didn’t matter anymore. I wanted to do this, however many rejections I faced.

A big concern was how to pay for this journey. I figured it would cost well over $100,000 to fly from state to state, stay in motels, and rent cars to drive to work. But I had no money. My first idea was to find sponsors. I contacted car dealerships, figuring that if one gave me a car, it would reduce the costs. I knew I’d need a car with enough room in the back for sleeping, to avoid spending money on accommodations. I contacted other potential sponsors as well, like energy drink companies, but from everyone, all I heard was “no.” So I looked for ways to greatly reduce the cost and make the journey “pay as I go.” I decided to drive from state to state and plan my route strategically to make the most headway in the shortest distance. This required coordinating the jobs based on the states I’d be passing through in a logical pattern so that it wasn’t too time-consuming, taxing, and expensive to drive from job to job. Even if I slept in the back of a car and avoided paying for motels, there would be substantial driving expenses, as well as other costs like food and insurance.

I knew it was critical to actually get paid, but I never outright asked employers to pay me because it was hard enough to land a job in the first place. I just wanted the job. But I hoped that if I performed well, they wouldn’t let me leave without giving me some sort of compensation. I couldn’t hold out any longer: I had to get out there and let whatever happened happen. I figured that if I started the journey, I could try to make ends meet on the road. Who knows? I might pick up a sponsor along the way. And even if I were to get paid, I had no way to estimate how much I would earn. But I figured that since I had been able to spend a week on vacation in Florida for under one hundred dollars, I might be able to do the same in every state. Plus, it had a nice ring to it: 50 Jobs in 50 States in 50 Weeks. I wouldn’t have guessed at the time, but as it turned out, I ended up working as a volunteer in just five states.

In the meantime, my parents were on the verge of kicking me out again. “Just one more month!” I begged. I made hundreds of calls per state in the four months since I started the project, willing to work in any state with any employer who could fulfill my objective. I had invested so much of myself that even after months of more rejection, I could not surrender. I knew I needed only one break for everything to fall into place. And sure enough, it was only a matter of time before my persistence finally paid off. I found the Nebraska Corn Board Association online and called to ask if anyone there knew of farmers I could work with for a week. A staffer put me in touch with a farmer who could use an extra set of hands. Soon after, I lined up a position at a general store in Montana during that state’s hunting season.

After setting up ten jobs, I knew I had to leave the house before another war broke out. I had no option but to set up the rest of my jobs while on the road. My brother opened a line of credit for me at his bank to purchase my first car. I maxed out the account with a $5,000 Jeep Cherokee. It was almost September and I was ready to start my journey, planning to hit the Midwest before the winter months. I called my local newspaper and it jumped on the story.

The article made front-page news and hit the wire to larger papers. Within days, a television producer contacted me about turning my idea into a reality show. Being the host of a television show about working across America was my dream and I was thrilled, but after giving it some thought, I realized that if a TV crew was involved, everything would change. People would treat me differently. I’d risk being scripted — or worse, I’d risk control over the project. I had already done the groundwork, lining up the first ten jobs through countless rejection. My life led me to this journey — all the failure, defeat, and struggle I’d been through had brought me here. I wanted to see it through the way I intended.

“Do you want your own show?” the producer of Dirty Jobs asked me. It was my dream come true — after searching for months for a sponsorship, finally, someone was interested. But this time, I wasn’t. I wanted to experience America, and no network or television show would direct my journey, or even tag along for the ride.