“非遗”档案:丽水鼓词

丽水鼓词,又称莲都鼓词,是丽水市及所属莲都(原丽水县)周围地区流行的一种民间曲艺形式。丽水鼓词盛行于清代嘉庆、道光年间,流传至今。丽水鼓词是一种表演时说唱相间的“说书”形式,当地人们又称之为“唱故事”,以丽水方言为鼓词唱念标准。演唱者多为盲人,且一人分饰多角,伴奏乐器为“鼓”和“六轮板”。演唱时呈坐势,左手握“六轮板”击强拍,右手持鼓箸敲鼓面。曲辞以七言居多,通常四句为一段。节目有长篇,也有短篇。传统节目的题材内容主要有侠义、公案、世情、神话等。鼓词艺人一般在人们一天辛苦劳作后或农闲季节走村串户演唱,演唱场所主要包括祠堂、弄堂、凉亭、戏台、农户家中堂。丽水鼓词已被选入第四批国家级非物质文化遗产名录。

The Intangible Cultural Heritage Archives: Lishui Guci

Lishui Guci, also known as Liandu Guci, is a kind of folk art in Liandu District, Lishui and its surrounding areas. It prevailed in the Jiaqing and Daoguang Periods of the Qing Dynasty and has been passed down to today. Lishui Guci is a genre of singing and storytelling in Lishui dialect, so natives also name it “story-singing.” Most of the performers are blind. The performer uses drum and clappers as accompaniment to the musical instruments and has to play all the parts himself. While performing, the performer sits on a chair with clappers on left hand creating a strongbeat and drumsticks on right hand to beat the drum. The lyrics are mostly seven-word sentences with four sentences forming a paragraph. There are long stories (Guci) and short stories (Guci) about folklore, legal cases, worldly affairs, fairy tales and so on. The Guci singer usually performs in the evening after people labour for a whole day or during slack seasons when people have leisure time, and the performance can be performed on a stage, or in a pavilion, ancestral hall or the hall of the farmer's house. Lishui Guci has been listed in the Fourth Catalogue of the State Intangible Cultural Heritage.

章永金:故事人的故事人生Zhang Yongjin: To Live with Stories

章永金,男,浙江丽水人。1949年,他师从王明昌先生。由于嗓音清亮、表演到位,是丽水鼓词碧湖腔代表人。2009年,凭《通济堰鼓词》获得了浙江省首批“优秀民间文艺人才”称号,是丽水市唯一获得该称号的人。2011年12月,被评为第三批丽水市非物质文化遗产“莲都鼓词”代表性传承人。2013年11月4日,被评为第四批浙江省非物质文化遗产“鼓词(丽水鼓词)”代表性传承人。

Mr. Zhang Yongjin comes from Lishui, Zhejiang. In 1949, he took Mr. Wang Mingchang as his master. Due to his clear voice and excellent performance, he is regarded as representative of Lishui Guci. In 2009, he became one of the first “outstanding folk art talents”of Zhejiang Province with his work,Tongjiyan Guci. Until now he has been the only one to win this title in Lishui. In December, 2011, he was declared a city-level intangible cultural heritage inheritor of Liandu Guci. On November 4th, 2013, he was declared province-level intangible cultural heritage inheritor of Lishui Guci.

故事人的故事人生

龆年终成鼓词人

7岁时,我突患眼疾导致失明。那个时候,由于医疗条件有限,后天失明的事情不在少数。这种情况下,家人一般会想两条出路,一个是去学算命,还有一个就是学习“唱故事”。我老爸卖肉种田,经济能力还算不错的,便送我去王明昌老先生那里学习鼓词去了。那个日子我记得很清楚,是1949年的农历三月三。

自古以来,唱鼓词的均是盲人,所以只有靠师傅口授,师傅一句一句教,我一句一句学,都是要记在脑子里的。那时,跟着先生一同学习的还有4位师兄(现均已逝世),学下来没多久,先生就发现我记忆超人。开始时,我们先学习小鼓词。先生将一本鼓词分成若干段落,一个段落分成四个小段,一个小段教三遍,一个段落记好了,再接着教下一段。四天下来,我就学会了一本鼓词。老先生惊讶之余,对我说:“小鬼,这样下去,两个月就给你学光了!”到了1951年3月,我已经会唱20本鼓词了。其间也跟着师傅或师兄外出表演。按习俗,学习期间外出表演所挣的钱也是要交给师傅的,只有这样,才算正式成为师徒。我记得,当时的学费为一年800斤稻谷(包括食宿),要学三年。但是到了1951年时,文化馆的新政策规定徒弟不用再给师傅交学费了。那时家里还欠先生300斤稻谷,老先生一看这个情况急了,说:“《陈十四夫人传》还有两段没交给你。这两段,你钱拿来,我给你教;你钱不拿来,我不教你。”我老爸就说:“照样给他!给他就是了!”这样我才学到了完整的《陈十四夫人传》。

丽水鼓词分为门头唱和坐堂唱两种形式。从演唱风格来说,主要有丽水调和碧湖腔两种。一本鼓词里,唱腔又可分为悲调、快活调、低调、高调等,分别表达不同的情境。丽水调和碧湖腔中,这四个调不尽相同。丽水鼓词的碧湖腔以节奏快为特点。还有过去老人唱的“三江韵”、“田江韵”、“七洋韵”。“三江韵”中“三江”即松阳、龙泉、青田三江并流,与沿江地区的方言相似,各地的人都能听懂。还有些地方小鼓词,没有书本,都是上一代老人们传下来的,如《贺亭会》、《血盘记》、《九龙鞭》等,一天可以唱好。大鼓词多为小说改编,例如《孟丽君》、《凤中龙》、《天宝图》等。其中《凤中龙》来自唐朝小说,一唱便要二十来天,《天宝图》为元朝鼓词,更是要一个多月才能唱完。我曾在碧湖从夏季唱到秋季,从农历五月一直唱到了八月十五中秋,白天休息晚上唱,那时候听得人也很多。演唱鼓词还需要配合表情、打鼓节奏使得情节更加动人心,否则就会显得平平淡淡。鼓词还分平态唱腔、流态唱腔、高态唱腔和行态唱腔,不同的唱腔用以表达不同的情绪,如《斩韩信》一曲中便配合情节发展,涉及多种唱腔,使鼓词表演更能感染人。由于鼓词艺术的独特与精彩,丽水鼓词于2014年入选了国家第四批“非遗”项目名录,我也由此成为莲都鼓词的传承人。

山重水复总有路

我还记得第一次登台演出大概在1949年8月份,唱的是《陈十四夫人传》。后来新中国成立,1950年,文化部组建了文化班学习些新的内容,走村进户地宣传党的方针政策。1951年7月起,我们学唱革命故事、反对旧封建势力这些内容。我们碧湖分会又分三组:云和一组、松阳一组、碧湖区一组,每组都有12人。那时候眼睛看不见的人很多,整个丽水协会有八十多人,几乎都为盲人,碧湖占三十多人。到了1953年下半年,县里搞起了互助组,三五人家为一个小组,实行共同劳动、换工互助,我们又开始宣传互助组的好处。1954年下半年,“同锅同勺”的日子到来,家中财物都要上缴,这种生活直到1955年下半年合作社成立才彻底结束。1957年,松阳县文化局邀请我去民间曲艺协会教一些盲人鼓词。之后,我才又迁回丽水。1958年,原来的生产队更名为生产大队,开始大炼钢铁。男女青年都外出造铁,我们就到田间地头宣传“人民贡献大家好”,晚上帮着生产大队剥玉米、产茶籽。配合运动宣传之余,平时大多演唱的是群众喜闻乐见的《珍珠塔》、《牡丹亭》等传统鼓词曲目和《碧湖景致》、《九龙鞭》等地方曲目。1966年“文革”开始,老鼓词被禁唱,只准唱《红灯记》、《智取威虎山》这类曲目。1969年,规定更加严格——老戏不准唱;男不得唱女,女不得唱男;正派不能唱反派,反派不能唱正派。当时剧团里多为女演员,哪来这么多人分角唱,曲艺协会就此解散了。

于是,我去了盲人工厂工作,劳动得食,一做就是十年。我和老伴儿两人拼命劳动,编麻绳,一月只有60元,可是这么点钱根本不够。老爸身患重病,家中还有两儿两女需要抚养。我迫于无奈,白天到厂里上班,早晨傍晚就挨家挨户上门唱小鼓词,讨一点米过活。当时,如果没有群众的帮忙,一家人早饿死了。也可以说是鼓词救了一家人的命。就过着这样拮据的日子,直到1979年8月,政策开放了,鼓词被允许唱了。有一天,村里人跑到我家中大声喊:“章永金,《红楼梦》、《麻花姑娘》、《哪吒》这些都能唱了,还在家里坐着干啥,出来‘唱故事’嘞!”我得知后,很是欢喜。在家里精心准备,挑了个日子,我便到村子里的一家小卖部门前重新开嗓了。首次开唱,我唱了《孟丽君》,村里人都开心得不得了,边拿着小说边听我唱,听我唱得对不对,听我有没有把人名唱错,有没有把情节唱漏了。《孟丽君》是大鼓词,一唱就连唱了5晚。那时候,电视还不常见,鼓词是人们辛苦劳作后的主要娱乐。在村民的强烈要求下,我又紧接着唱了《天宝图》。从1979年到1988年,鼓词一直在农村深受群众的欢迎。上门来请我去唱的人都特别多。1988年后,电视开始在农村普及,听鼓词的人渐渐少了。到了20世纪90年代后,鼓词艺人和听众都后继乏人,处于濒危状态。我带着几个徒弟,主要唱一些村民还愿时听的《陈十四夫人传》、《观世音》等少数几个曲目。

愿得新景万木春

1988年,丽水文化馆的领导找到我,要我为通济堰这一处古迹编一段《通济堰鼓词》。当年的重阳节我就在通济堰搭的台上唱了这首,唱的是通济堰的故事来历,还做成了录像。我后来多次修改《通济堰鼓词》,2009年,凭此作品获得了浙江省首批“优秀民间文艺人才”称号,是丽水市唯一获得该称号的人。后来,随着政府对非物质文化遗产越来越重视,我在2011年及2013年,先后被评为第三批丽水市非物质文化遗产“莲都鼓词”代表性传承人,第四批浙江省非物质文化遗产“鼓词(丽水鼓词)”代表性传承人。也正是政府乃至整个社会对“非遗”的重视,让丽水鼓词又重回人们的视野。前前后后,我已经接受过不下十次的采访了。最近的一次是2015年6月底,杭州的学生前来了解丽水鼓词。

这两年,保护这一方面,已经有所起色了。丽水文化馆,“非遗”中心都有来找我,从我口中了解丽水鼓词,让我口述记录一些曲目,但借此保存下来的曲目毕竟是少数。如今我年纪大了,记性也大不如从前。最多的时候,能唱一百多本鼓词呢!现在,脑子里记住的,只有三四十本了。随着年岁的继续增大,不出几年,可能都会忘掉,而鼓词又是口口相传的,实在是很担心有些鼓词传到我这一代就难以为继了。至于传承,目前鲜有成效。我带过五个徒弟:余大优(现已去世)、陈加贵(现已去世)、王名平、吴春明和庚建军,均为盲人。眼睛看得见的、有文化的更容易学习鼓词,可惜基本没人愿意学。我收徒要求并不高,只要听听嗓子好不好,够不够清亮便可。据我了解,温州有的茶馆历来就是有鼓词表演的,人们喝着茶,听着鼓词。可惜丽水没有这样子的习俗,也就失去了这么一个舞台。丽水鼓词需要探寻自己的发展方向。我已经老了,希望能有年轻人将之带到更大的舞台。

To Live With Stories

A Gifted Teenage Guci Singer

When I was seven, an accidental eye disease resulted in my blindness. At that time, due to the limited medical condition, becoming blind was quite common. In such cases, the families usually would come up with two solutions: One was“fortune-telling”, the other was “story-telling”. Luckily, my family was better off enough to send me to master Wang Mingchang's home to learn Guci on March 31st, 1949, which is an unforgettable day for me.

Since ancient times, the Guci performers were the blind. As a result, all the teaching was based on verbal instruction. That is to say, the master teaches one sentence, and the disciple learns and memorizes it. In those days, four other disciples were studying with me. It did not take my master a long time to discover my striking memory. At first, we started from short stories. Master Wang divided one story into several parts with one part consisting of four paragraphs. Each one was taught three times. Only after we remembered the present one, could we move to the next. After only four days, I learned one whole piece of Guci. In great amazement, Master Wang said:“Kid, if you keep on learning like this, you are going to finish the learning in two months.” When it came to March 1951, I was already able to perform twenty stories. During that time, I, together with my master and the other four disciples, went on the road to act as well. According to custom, all the money earned during the learning period should be given to the master, which was essential to establish a stable master-disciple relation. I remember I had to learn for three years altogether, and my parents would give 400 kilograms of unhusked rice as tuition to my master. But in 1951, the local cultural center issued a new policy, stating that disciples do not have to pay the tuition anymore. As soon as my master heard the news, he threatened:“There are still two parts of The Legend of Lady Chen Shisi that you haven't learned. No payment, no teaching.” Then my father said:“Just give him the money!” Thus, I acquired the complete version of The Legend of Lady Chen Shisi.

The two forms of singing Lishui Guci are called “singing in the doorway” and“singing in the hall.” In other words, Lishui Guci can be performed both in public and in private. According to the dialects performers adopt, it can be divided into two types:Lishui accent and Bihu accent. In a piece of Guci, the tune can be sad or happy, bass or treble to express different emotions. The four tunes are different in Lishui accent and Bihu accent. The Bihu accent of Lishui Guci is characterized by its fast rhythm. And in the past, the old artists sang “Three-River Rhythm,” “Tian River Rhythm” and “Qiyang Rhythm”. The three rivers of Songyang, Longquan and Qingtian flow together, and dialects are similar in these areas, so people of those areas can make sense of it.

There are long stories (Guci) and short stories (Guci). No books can be found for some short Guci. These are passed down verbally from earlier generation, such as Heting Gathering,Blood Dishes,Dragon Whip and so on. The performance can be completed within a day.The long stories were novel adaptations such as Meng Lijun, Dragon Phoenix and Tianbao Painting.The Dragon Phoenix was adapted from Tang Dynasty novels and usually takes more than twenty days to perform while Tianbao Painting was created from Yuan Dynasty novels and even takes more than one month to perform. I once sang Guci in Bihu Lake from summer to autumn, from the fifth lunar month to mid-autumn. I rested by day and sang at night. There were many listeners. Also, facial expression is an indispensable part of singing, and the rhythm of drumming makes stories more touching, or it will be too plain. Guci also has a flat tune, a flowing tune, a high tune and a progressive tune to express different emotions. For example,Behead Hanxin should be sung in several kinds of tunes to coordinate with its plot, making it more vivid. Thanks to its unique style and wonderful performance, Lishui Guci was listed in the Fourth National Catalogue of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2014. And I was declared an inheritor of Liandu Guci.

A Way Out of a Dilemma

I still keep my debut in memory.It was in August of 1949 when I performed The Legend of Lady Chen Shisi.Later the People's Republic of China was founded and in 1950, the Ministry of Culture set up a training course for us to learn some new content in order to publicize the Party's general and specific policies from one village to another. From July 1951 on, we started to put on shows about revolutionary stories, opposition to the old feudal forces, and so on. The Bihu branch was divided into three groups: Group Yunhe, Group Songyang, and Group Bihu. Each group consisted of twelve people. At that time, the whole association had eighty members, nearly all blind. In the second half of 1953, our county government recommended that we found mutual aid teams, and each had three to five households. People on the same team worked together and helped each other. Hence, we began to publicize the benefits of mutual aid. In the second half of 1954, the days called “Eat with One Pot” came. All family property had to be turned over. Life like this did not end until the second half of 1955 when cooperatives were established. In 1957, the Cultural Affairs Department of Songyang County invited me to teach some of the blind in the Folk Art Association, and then I was placed on the staff of the department. Sometime later, I moved back to Lishui. In 1958, the original production team was reformed into a production brigade, and then came the Great Steel-making Movement. In the daytime, young men and young women were out for steelmaking, and we, the blind, went to the fields to propagate “One for All, All for One”. At night, we helped the production brigade to shuck corn and pick tea seeds to produce tea seed oil. Beyond our propaganda, we often performed some traditional Guci such as Pearl Tower,Peony Pavilion,and some local Guci like Bihu Scenery and Dragon Whip. In 1966, the“Cultural Revolution”began.As Guci was banned,we could only sing the tracks like The Red Lantern and Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy.In 1969,more rules were given:Old operas were not allowed to be sung; males could not play female roles; females could not play male roles; positive role players could not play villains, and vice versa. At that time most players were female, and there were not enough actors to perform different roles, so the opera association was dismissed.

Then I had to support my family by working in a factory for the blind where I worked for ten years. My wife and I both knitted ropes which was a very hard job but poorly paid. We could only get 60 yuan a month. The salary was too low to support us. My father was seriously ill, and I had two sons and two daughters to raise. Apart from the daily work in the factory, I had no choice but to sing Guci for my neighbourhood after work in order to beg for some rice. Without the villagers' help, my family might have starved to death. Eventually it was Guci that saved our lives. In August of 1979, such financial hardship came to an end. The policy was revised, and Guci was allowed to be sung again. One day, a villager ran to my home and shouted:“Zhang Yongjin, A Dream of Red Mansions,Girl with Dough-twist Style Plait,and Ne Zha are all allowed to be sung again. Why are you still sitting there? Come out and sing for us!” I was so happy to hear this! Getting carefully prepared at home and choosing a date, I started to perform in front of a grocery shop.The Meng Lijun that I sang brought the villagers much joy. You could see some of them holding the novel open in their hands when they were listening to check whether I sang it correctly, whether I remembered the names of the roles and whether I missed any of the plot.Meng Lijun is a long story that took me five nights to perform. At that time television was not prevalent, so Guci was the main entertainment after a long day of work.At the insistent request of the villagers,Meng Lijun was followed by Tianbao Painting immediately.From 1979 to 1988, Guci was warmly welcomed again among villagers. Many people came and invited me to perform. After 1988, television prevailed in the rural areas. As a result, the audience for Guci was on the decline. Through the 1990s of the last century, both Guci performers and audience lacked successors, and Guci was on the verge of extinction. At present, several disciples and I merely perform a few tracks that people required for religious reason,such as The Legend of Lady Chen Shisi and Guanyin.

A Sincere Wish for Guci

In 1988, the Lishui Cultural Centre invited me to write a piece of Guci about how the Tongji Yan, a historic site, came into being, called Guci of Tongji Yan. On the Double Ninth Festival of that year, I played this new show at Tongji Yan, which was recorded on video. Afterwards, I made several necessary corrections. In 2009, I was declared one of the first “Outstanding Folk Art Talents” of Zhejiang Province in virtue of this work. Until now I have been the only one to win this honorary title in Lishui. As the government attached more importance to the intangible cultural heritage, in December, 2011, I was declared the representative inheritor of the Liandu Guci, the third cohort intangible cultural heritage of Lishui. Then on November 4th, 2013, I was declared representative inheritor of the Guci (Lishui Guci), the forth cohort intangible cultural heritage of Zhejiang. The increasing attention that the government and society in general paid made Lishui Guci the focus of public concern. So far I have been interviewed no less than ten times. The latest one was in June, 2015, when students from Hangzhou came to catch a glimpse of Lishui Guci.

Actually, as far as the protection of Lishui Guci goes, there have been some good signs over the last few years. Many organizations, such as the Lishui Cultural Centre and the Intangible Cultural Heritage Centre, came to interview me about Lishui Guci. What's more, some tracks were put on record through my dictation. In spite of that, only a small minority of Guci can survive. When I was young, there were more than 100 tracks in my mind, but now I am too old to have a good memory. Many tracks keep escaping my mind, so I merely remember two fifths of them at present. Since Guci is passed down by oral teaching, I do worry that the inheritance will be hard to sustain. For inheritance, no clear successor has appeared. I have five disciples: Yu Dayou, Chen Jiagui, Wang Mingping, Wu Chunming, and Geng Jianjun. All of them are blind. No doubt it is much easier for those who are not blind and have been properly educated to learn Guci. However, no one is willing to learn. The requirements to become my student are not so high. A clear voice will do. In addition, I have learned that in Wenzhou, Guci and teahouses are a pair like a fork and a knife. People sit there, drinking tea and appreciating the lingering charm of Guci. Unfortunately, there is no such a tradition in Lishui. Therefore, there is no such stage for Lishui Guci. Maybe we need to explore a unique manner of inheritance for Lishui Guci. I am not young any longer. I hope the younger generation can bring it to a broader stage.

“非”入寻常百姓家

走近鼓词,如同走近一座充满故事的古城,我们不知所措地在城外徘徊,直到遇到章永金老先生。从他的故事人生里,我们读到了鼓词的温度,也尝试着思考与这项古老艺术形式相关的种种。

7月10日的细雨中,我们一行五人出发前去拜访章永金老先生,他的家在碧湖镇一条老街上。这是一个充满年代感的地方,窄窄的街道,两边立着低层木质楼房。夏日里,街道两侧的梧桐树绿得望不见尽头。在这里,聚在门口斗棋的三五老大爷,坐在小卖部门口拿着蒲扇的老婆婆,高高悬着的算命取名招牌,关了门的供销社和美发廊,都见证了丽水鼓词繁盛的过去,如今又如这条老街一样的安静。

章老先生用整整一个午后与我们分享了丽水鼓词与他的故事人生。章老先生满头银发,身材魁梧,声音洪亮且底气十足。丽水鼓词大概是老人家一生最为骄傲也是最为熟悉的东西,谈起鼓词便是滔滔不绝,其间还频频插入几句鼓词的演唱,让人觉得这已是他生命的一部分。访谈结束时,天大晴,晚霞似乎驱散了缭绕着丽水鼓词的层层迷雾,但我们的脚步却轻快不起来,思绪还停留在老人的话语中。

通过老先生学艺、从艺、授艺的一生,我们了解到在那个多数人不识字的年代,鼓词是艺人赚钱养家的手段,也是大众辛苦劳作后的娱乐方式,它是传递健康价值观的载体,帮助人们明辨是非。然而,谈到丽水鼓词的传承,章永金老先生面露忧容,“如今会唱丽水鼓词的人在少数,精通的更是寥寥无几,且都年事已高。丽水鼓词恐怕很难传承下去。”这种担忧不无道理,随着当代社会经济、科技的飞速发展,人们娱乐生活愈发丰富多样,将注意力放置于非物质文化遗产的人少之又少。鼓词传承面临的困境亦是众多“非遗”项目的写照,我们有必要认真思考保护和传承“非遗”的意义。

首先,非物质文化遗产是我国传统文化的重要组成部分,是中华民族身份的象征,是文化认同和文化自信的源头。中华上下五千年,点点滴滴的文化沉淀奠定了今日中华文化在人类社会中与众不同的地位。中华文化是由各族文化、各地文化汇聚而成,丽水鼓词是丽水地方文化中浓墨重彩的一笔。丽水鼓词演唱时以丽水方言为唱念标准,想必,只有丽水民众才能真切地晓悟其中韵味。

其次,非物质文化遗产是一部活态的民族历史教科书,它鲜活地传承着丰富的民间历史。不计其数的书籍,固然为我们提供了一窥历史真相的机会,但在那些个时代,撰写历史的权利基本上都掌握在统治阶级手中,记载的多是王侯将相的生活,缺少了作为大多数民众的日常生活。由此,非物质文化遗产就成为探寻历史的绝佳渠道。从唱婚姻法到互助组以及改革开放,章老先生的鼓词人生便承载了丽水历史文化的一部分。

第三,非物质文化遗产具有再创造性,是文化创新、艺术创新、科技创新的需要。有人可能会质疑:丽水鼓词已然是被现代社会所淘汰了的娱乐方式,理所当然随历史洪流而去,退出历史舞台。为什么还要花费时间、金钱去保护,甚至去传承它?全球化发展到现在,我们确实借鉴外域文明实现了众多创新,但是切勿否定传统文化成为新文化基因的可能性。正如黄永松先生所说:“传统文化是救赎之道。”

“旧时王谢堂前燕,飞入寻常百姓家。”作为曾经民众日常娱乐的重要方式,“非遗”项目应该从群众中来,到群众中去。交谈中,章永金老先生提到,丽水鼓词多为盲人演绎,且只有依靠上一代艺人传授的唱腔来传承,要传下去难度较大。他提到温州鼓词的发展,主要是学唱的艺人学历较高,许多并非盲人,可对书演唱,并且当地形成了茶馆内听鼓词的习惯。人们来茶馆喝茶,边喝茶边听鼓词,鼓词艺人可以此谋生。这也不失为一种传承方式。传承人是非物质文化遗产保护的重心,在生活有保障的前提下,才有人愿意传承它。说到底,“非遗”离生活越近,其传承越容易获得老百姓包括年轻人的认可和尊重。

The Approach to Intangible Cultural Heritage

Approaching Lishui Guci is like walking up to an ancient city full of stories. We wandered outside of the city at a loss until we came across Mr. Zhang Yongjin. Through his story life, we perceive the true charm of Lishui Guci. Furthermore, we try to ponder this aged art form and the things related to it.

In a steady drizzle on July 10th, five of us set out to visit Mr. Zhang Yongjin. His home is situated in an old narrow street of Bihu with low wooden buildings standing on both sides. During the summer, neatly-spaced plane trees color the entire street green, seemingly endlessly. It is a place where you can find the traces left by time. Here, four or five old men sit in the doorway and play chess, an old lady sits in front of a store and holds a palm-leaf fan, a signboard that announces fortunetelling hangs high above the street, and a trading cooperative and a salon are closed. All of these witness that Lishui Guci thrived once, but now is as quiet as this old street.

Mr. Zhang spent a whole afternoon sharing his story about Lishui Guci with us. He is stout with grey hair and has a stentorian voice. Since Lishui Guci is so familiar and such a proud thing for him, there was no holding him back when he spoke. During the conversation, now and then he could not help singing for a while which made everyone understand this had been an indispensable part of his life. Soon the interview came to an end, and the weather cleared. The interview seemed to be like the sunset that dispersed the thick drizzle around Lishui Guci. However, with heavy hearts, we were immersed in what the old man said.

From his lifetime of learning, performing and imparting Guci, we learned that in those years, when most people were illiterate, Guci was not only a way for performers to make a living but also an entertainment for folks after a day of toiling. Most importantly, it made healthy values accessible to the illiterate. However, when we speak of the inheritance of Guci, Zhang looked worried:“Nowadays only a few people can sing Lishui Guci, and even fewer people are expert at it. What's worse, they are all long in the tooth. I am afraid it is difficult to pass it down.” Such worry is undoubtedly logical. With the rapid economic and technological development of modern society, people's entertainment is more diverse, so very few people are willing to put their focus on intangible cultural heritage. The dilemma of Guci is an epitome of all intangible cultural heritage. Thus, it is essential for us to reflect on the protection and preservation of intangible cultural heritage and the significance of this work.

First of all, intangible cultural heritage is part and parcel of Chinese traditional culture, a symbol of the national identity, and the source of cultural identity and cultural self-confidence. For 5,000 years of Chinese civilization, culture has accumulated bit by bit which gives Chinese culture a distinctive status in human society today. No doubt Chinese culture is a bringing together of every ethnic culture and folk culture. Lishui Guci is a significant element of Lishui culture. Now that Lishui Guci takes Lishui dialect as the singing standard, presumably, only local people can savor the lingering charm of Lishui Guci.

Second, intangible cultural heritage is a textbook of living national history. It vividly records various colorful folk histories. Of course, countless books provide us a glimpse of the historical truth, but in those times, the right to record history mostly rested in the ruling class, and they mainly recorded their own lives which lacked the great majority of the common people's daily lives. As a result, intangible cultural heritage has become a great means to explore the history of the common people. From singing of the marriage laws, mutual aid teams and the Reform and Opening-up, Zhang's life of Guci carries a large part of Lishui history and culture.

Third, intangible cultural heritage has the function of recreation that is needed for cultural, artistic and technological innovation. Some people might question that since Lishui Guci has already been eliminated in the tide of modern society, it is natural for it to disappear from the historical stage. Why should we spend time and money to protect it or even inherit it? In the age of globalization, we do need foreign civilization for reference to realize our innovations. Yet, at the same time please do not deny the possibility that traditional culture can be the gene of new culture. Just as Huang Yongsong said, “The way of salvation is traditional culture.”

The ancient Chinese poet Liu Yuxi wrote, “The swallows that used to be housed with the wealthy are now flying into the homes of ordinary people”. As a former daily entertainment, intangible cultural heritage should be “from the masses, to the masses”Zhang Yongjin mentioned that the performers of Lishui Guci are mostly blind, and the art is only passed down from mouth to mouth which makes it more difficult to inherit. He referred to the development of Wenzhou Guci. The learners are well educated, and many of them are not blind; that is to say, this fact allows them to sing by means of books. Moreover, there is the habit of listening to Guci in the teahouse. People come to the teahouse to drink tea, and they listen to Guci at the same time. On one hand, performers can make a living by virtue of this. On the other hand, this can be regarded as a way of inheritance. Inheritors are essential in the process of intangible cultural heritage protection. Only when the living conditions are guaranteed, are the inheritors willing to learn and to inherit and promote Guci. In the last analysis, the closer intangible cultural heritages are to ordinary people, the easier Guci is to be accepted and respected by people, including the young.

黄景农:一生的追随Huang Jingnong: A Lifetime of Artistic Pursuits

黄景农,男,浙江丽水人。11岁开始拜师学艺,13岁登台演出,从事鼓词演唱70多年。2011年被评定为市级非物质文化遗产项目代表性传承人,代表项目为莲都(原丽水县)鼓词。2013年被评定为省级非物质文化遗产项目代表性传承人,代表项目为丽水鼓词。先后获“国际中华优秀作家”、“中国十大民间艺术家”、“国家文艺功勋人物”、“中华杰出爱国人士”等荣誉称号。

Huang Jingnong comes from Lishui, Zhejiang Province. He began to learn Lishui Guci when he was eleven years old, and two years later, he started his Guci career. He has been engaged in Guci performance for more than seventy years. He was declared the representative inheritor of Liandu Guci at the city level in 2011 and the representative inheritor of Lishui Guci at the provincial level in 2013. He has been awarded the “International Chinese Excellent Writer”, the “China Top Ten Folk Artist”, the “National Meritorious Artistic Figure”, the“Chinese Outstanding Patriot” and other honorary titles.

一生的追随

学艺:少年的选择

我出生在一个普通人家。我的左眼是出生的时候就看不见东西的。等我长到十来岁,还在上小学的时候,我的父母就找到了我的师傅,把我送到他那里学习鼓词。我也喜欢听鼓词,那时父母说要送我去拜师学唱鼓词,我是很高兴的。我的师傅叫金细宝,是丽水市城关镇人。师傅他从小就跟着丽水鼓词名伶王志良学唱鼓词。功底扎实,水平很高,尤其擅长说唱丽水鼓词的当家曲目《夫人词》,他与我的师公都以擅长编写而闻名于丽水词坛。因为师傅的影响和指导,后来我不仅传唱经典曲目,同时也进行鼓词创作。

那时候学习唱鼓词一般都是眼睛有疾病的人,以求学一技之长能够谋生。离我小学毕业还有一些日子的时候,我的眼睛已经不像其他正常的孩子,父母担心我的未来,所以很鼓励我学唱鼓词。他们为我找了师傅,带我去拜师,我的小学也就没再上了。我从11岁开始跟着师傅学唱鼓词,当时拜师学艺要写投师贴,要交教工金10~15块银圆,还要请同行的伙伴吃入学酒。除此之外,家里要设立“夫人坛”。鼓词需要唱会全本的《夫人词》和十几首短鼓词才算出师。师傅一句一句教,我一句一句学。那时候学鼓词都是这么个教法,没有唱本,只有口口相传。所有的唱本都是记在脑中。因为当时年纪轻,我又很喜欢鼓词,所以学起来很快。跟着师傅学了三年,13岁学成出师。出师的时候也要请谢师酒,以得到同行的承认。还有,以前的惯例是每年的农历七月七日,全体鼓词艺人在夫人庙会面,集中交流经验和商议行业内部事务。

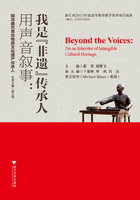

丽水莲都鼓词道具板与鼓

从艺:壮年的沉浮

新中国成立初期,丽水县大概有鼓词艺人70多人。为了使民间这支文艺队伍更好地为社会主义服务,文化部门曾多次组织学习和培训,我同我的师傅一起参加文化馆举办的各期盲艺人讲习班。当时丽水文化馆不仅组织学习和培训,还组织鼓词艺人们进行新鼓词的创作。由鼓词艺人们创作曲目,再由相关工作人员做记录,写下来。当时鼓词艺人们唱的新短鼓词大致有:《新旧社会比一比》、《翻身小唱》、《刘胡兰》等。新长鼓词大致有:《白毛女》、《三世仇》、《两兄弟》等。在党和国家的带领下,丽水鼓词的盲艺人对各个时期的工作进行积极的配合,创作出了大量顺应时代潮流,歌颂新社会的鼓词。

到1954年,“丽水县盲鼓词艺人协会”正式成立。经民主推选,我很荣幸当选为协会主任,同仁中还有赵金余、傅三豹和赵金水等。1956年,浙江省第三次戏曲工作会议召开,丽水鼓词协会委派我作为代表出席参加。鼓词艺人有了自己的组织以后,我们就可以更好地处理同行中的一些事务,一起交流学习。

那时候学唱鼓词的氛围是好的,生活条件虽不太好,也不算困难。但是“文革”期间禁唱传统鼓词,鼓词艺人要么改行,要么失业。我从没有想过要改行,所以一直在三里亭外给人烧开水。那时,鼓词艺人们的生活必然不好,人们之间也没有了交流,鼓词得不到传承和发展。禁止鼓词的演唱是我遇到的最大的困难。这三千多个日夜,是我一生的最痛处。

不过那段时间虽然苦,也熬过来了,从此可以更好地演唱鼓词了。

传艺:暮年的追求

改革开放后,民间的艺术也不再被禁止,一些鼓词老艺人又重新开始唱鼓词。我一听说可以再唱鼓词了,立刻重新拿起了切,敲起了鼓。但是这个过程中,很多鼓词艺人都改行了。随着时间的推移,唱鼓词的艺人慢慢地减少。而且现在的人也没有像以前那么爱听鼓词了,电视、电影等的普及,演唱者的减少和听众的消失都使得鼓词这样比较古老的艺术逐渐受到冷落。种类繁多的曲目也渐渐被人淡忘。很多曾经只靠口口相传的曲目都消失了,只剩下一些比较经典的曲目还在传唱,比如长鼓词《陈十四夫人传》——陈十四夫人曾是丽水地区人人皆知的美丽传说。1995年3月,中国文学家学会、浙江省与福建省、上海文艺学会以及日本有关研究人员,出于对丽水鼓词的保护找到了我,由我唱述,由唐宗龙、李蒙惠记录,共同出版了《陈十四夫人传》一书,全书8万余字。

总有一些场合还是会需要请人表演鼓词,比如说,像小孩子出生了,日常娱乐,红白喜事和求神祈福,就会请人唱鼓词。这是习俗,更是一种仪式,具有祈福的意味。我现在没有徒弟,但是时常会有一些年轻人找到我。他们大多因为兴趣而来,让我教他们唱一些比较简单的鼓词。现在学习鼓词的不仅有盲人,也有眼睛好的人。

因为现在年纪大了,腿脚也不太方便,现在一般不太出门。但我的右眼还能看见一点点的光线,我还可以在家里进行鼓词的创作。鼓词已经是我生活的一部分了。也许到我拿不动笔的那天我才会停下创作。这也是我现在能为传承鼓词而做的为数不多的事情了:留下古老的唱本,写下新的唱词,为后辈留下些东西。

同时政府及相关部门也越来越重视鼓词的保护和传承。鼓词也被列为非物质文化遗产。文化馆的工作人员经常举办鼓词活动,电视台也会宣传。鼓词有着它自身的特点,并不会被其他艺术形式所替代。我们现在可以做的,就是保护好它,保存好它。像《陈十四夫人传》唱本,用笔和纸记录下来,就不会再流失了。

左为黄景农版《陈十四夫人传》,右为黄景农先生所创鼓词唱词

A Lifetime of Artistic Pursuits

The Choice of Childhood

I was born in an ordinary family. Unfortunately I am blind in my left eye, so I can see only with one eye. When I was ten years old, still in my elementary school days, my parents found a master for me and sent me to the master's home to learn Guci. I have always loved to listen to Guci since I was very young. Thus, when my parents told me that they would send me to learn to sing Guci, I agreed at once. The master, my teacher, was called Jin Xibao. He lived in Chengguan Town of Lishui and learned Guci in his childhood from a famous actor of Lishui called Wang Zhiliang. Jin was a high-level master especially in singing The Lady Lyrics, one of his most adept programs. Both of them were famous for creating new lyrics in the field of Guci in Lishui. Under the influence and guidance of my teacher, I later began to sing classical lyric of Guci and to create new items of Guci as well.

People who learned to sing Guci at that time were generally those with eye problems. It is a good choice to have a skill in order to make a living. Since my eyes were not like those of normal children, my parents were so worried about my future that they encouraged me to learn to sing Guci and found a master for me. At the age of eleven, before graduating from elementary school, I quit school and started to follow the teacher to learn Guci singing. If a person wanted to learn Guci singing and to be a disciple of a master, he had to hand in Toushitie first, a kind of letter to express his desire to take someone as his master. Then, he had to give ten-to-fifteen silver dollars for tuition and invite his Guci fraternity brothers to a formal dinner. In addition, the disciple's home was required to set up a kind of sacrificial altar named “The Lady Altar”.I did all those things.Then,only when I could sing the whole Guci The Lady Lyrics and over ten short Gucis could I finish my studies.I learned in this way:When my teacher sang a sentence, I learned it and kept it in my mind. There was no other way of learning at that time. All of the librettos were learned by heart. All of the Guci was passed from mouth to mouth. Because I was young and liked Guci, I learned quickly. When I was thirteen years old, I finished my studies and could perform Guci alone. Finally, I invited my master and my fraternity brothers to the Dinner of Thanks to get their recognition.

In addition, another practice involved all the people who were engaged in singing Guci to meet in the Lady Temple to exchange their experiences and deal with internal affairs on the seventh day of the seventh month every year of the lunar calendar.

The Ups and Downs of Adulthood

When the P. R. China was established, there were about seventy Guci artists in Lishui County. In order to improve the Guci artistic team, the Lishui cultural department repeatedly organized those people for training. My teacher and I participated in the activities together. At the same time, we were organized to create new librettos for Guci. When a new libretto was created, the department staff wrote it down while we sang it. The new short Guci librettos were The Comparison between Old Society and New Society,Sing for Liberation,Liu Hulan and so on.The new long ones were The White-Haired Girl,Three-Generation Hatred,Two Brothers and so on. Under the leadership of the Party and the country, Lishui Guci artists created many new works to sing high praise for the new society.

By 1954, the Blind Artist Association of Lishui Guci was formally established. It was a great honor for me to be elected director of the association. Other leading members were Zhao Jinyu, Fu Sanbao and Zhao Jinshui and so on. In 1956, Zhejiang Province's Third Opera Conference was held. The Lishui Guci Association appointed me as a representative to attend the conference. With our own organization, we could share experiences and deal with internal affairs better than before.

At that time we had a pleasant atmosphere in which to sing Guci, although the living conditions were not so good. However, during the “Cultural Revolution”, most of these kinds of entertainment were forbidden, of course Guci included. Many artists could not sing Guci anymore. They became either jobless or changed their profession. As for me, I never thought of giving up singing Guci, nor did I want to change profession, so I chose to boil water to make a living. Our life was so hard, but the most terrible thing was that there was no communication between Guci artists. No one taught it, and no one learned it, either. Guci was lacking in development and inheritance. This was the most difficult period I have ever experienced. What I suffered most was that I couldn't sing my Guci in those days.

However, after ten years, the hard times were gone, and I could sing Guci again.

Pursuits in Old Age

Since the Reform and Opening-up in China, folk art was no longer banned. Artists gradually began to sing Guci. I had no sooner heard the news than I started to sing Guci. As time has gone by, the number of Guci artists gradually diminished. Now, people do not like listening to Guci as much as before. With the popularity of film and television, people prefer watching television and movies. Reduction in the number of performers and audiences has gradually made it fall out of favor. A variety of repertoires also have gradually been forgotten. Only some of the classical songs are still being sung, such as The Legend of Lady Chen Shisi that is a well-known and beautiful legend in Lishui. In March 1995, a group of people, for the purpose of the protection of Lishui Guci, visited me. Some were the members of the Chinese Literary Institute, some were the members of the Literature and the Art Society of Shanghai, Zhejiang and Fujian Provinces, and others were art researchers from Japan. They arranged for me to sing this famous piece and asked Tang Zonglong and Li Menghui to write down and collect the libretto. We jointly published an 80,000-word book entitled The Legend of Lady Chen Shisi.

However, on such occasions as the birth of new babies, daily entertainment, weddings and funerals and so forth, local people still need artists to perform Guci. This is a custom, but also a ritual, to express their blessings and prayers. I have no disciples. Nevertheless, some young people who are interested in Guci often come to see me and ask me to teach them to sing some simple lyrics. In addition, Guci is now studied not only by the blind but also by able-bodied people.

With getting older and some trouble in my legs, I have to stay at home now. However, my right eye can see a glimmer of light. I can still write new lyrics for Guci and produce new works at home. Guci has always been a part of my life. I know that I won't stop writing until I am not able to write. This is one of the few things I can do for the preservation of Guci: Saving ancient Guci and creating some new. This is what I can leave for successors of Guci.

Nowadays, the government and departments concerned paying more and more attention to the protection and inheritance of Guci. Guci has been listed in the catalogue of the national intangible cultural heritage list. From time to time the Lishui Cultural Center carries out activities for Guci. Television stations often broadcast it as well. Guci has its own characteristics, and I believe that it will not be replaced by other arts. Now what we can do is to protect it, save it. Just as we wrote down the story of Chen Shisi, we also can write down, tape and video other Guci items so that Guci will have a new life in the future.

吟唱一生

一个人,一面鼓,一把切,一张嘴,一生吟唱,一世牵挂。配合着鼓声中节奏分明的节拍,黄景农先生就这样在近八十年的时光里吟唱着鼓词。尽管前路漫漫,遥遥无期,追求梦想的心不会改变。鼓词生涯,就此拉开序幕,至今也没有结束。

七月初的一个日子里,我们一行人在淅淅沥沥的小雨中追寻鼓词的足迹,寻找省级非物质文化遗产项目代表性传承人黄景农先生。当门被打开的那一瞬间,我努力抑制着内心的激动。听到黄景农先生亲切的问候,看到夫妇俩满面的笑容,几个星期的寻访、联络有了存在的意义,困扰内心的焦虑也渐渐缓解。

黄景农先生家里很是干净和温馨。我们进门的时候,黄老先生正坐在餐桌边上。黄老先生的妻子边朝客厅的沙发走去边说着什么。翻译(由于我们和传承人之间语言不通,所以我专门找了当地的一个同学帮忙,陪同我们一起去寻访传承人)告诉我们黄先生的妻子是在邀请我们坐到客厅的沙发上。虽然我听不懂她说了什么,但是从她真诚的笑容里,我读懂了:“非常欢迎你们!”

蒙蒙细雨洗去了城市的浮华和喧嚣,我即将要接受一场艺术的洗礼,内心不免有些激动和兴奋。在来之前,我一直担心语言不通,交流不便的问题。但是看到两位和蔼的老人家时,我突然想起来,之前委托翻译给黄老先生打电话,表达我们的拜访之意的时候他说的一句话:“好的,好的。我牢记那天早上不出门。”多么可爱善良的一位老先生!似乎没有什么好担心的了。

进了客厅,我立刻发现客厅的两面墙上挂有一些照片和荣誉证书,好奇之下急忙询问老先生那些是什么照片。而此时黄老先生正一手拄着拐杖,一手在妻子的搀扶下颤颤巍巍地走向客厅里的沙发。黄老先生已是85岁高龄,所以腿脚有些不便,走路很是吃力。但是他听到我们的询问,还没走到沙发边坐下就开始给我们讲墙上照片的故事,每一个故事都离不开鼓词。从老先生的故事里,我所感受到的是他对鼓词发自骨子里的热爱。因为别人心中的丽水鼓词,是文化;而他心中的丽水鼓词,是生活,这一辈子的生活。

待每一位队员就位后,我们便开始坐上时光机,与老人一起回到过去。因为老先生的听力不太好,整个过程中都半侧着头极认真地听我们说话。一开始的时候他并没有太多的话语。但是一说到鼓词,老先生似乎变得更精神了,手扶着座椅的把手,直起身子,微微地向前挪动。其间,他还不时站起身走向房间,待转身出来,手上拿着书或资料。原来是因为和我们聊到一些话题,他想到有资料可以看,就赶忙起身去拿给我们。

在老人拿给我们的一叠书和资料里,我很惊讶地看见不少的荣誉证书,还有很多的稿子。原来这些稿子都是老人自己创作的鼓词。有一些稿子是打印的,有一些稿子是手写的。每一份稿子的右下角都有老人的名字和创作的时间。最新的一部作品是在今年创作的。而荣誉证书里有很多都是因为创作获的奖。无法想象一个与鼓词相伴74年的85岁老艺术家对鼓词的热爱到底有多深。当鼓词已经融入老先生的血液中,成为他生命中不可分割的一部分的时候,任何困难都不足以妨碍他对鼓词的热爱,年迈的身体也难让他在艺术的道路上停止奔波一生的步伐。

一个人为了鼓词,一生吟唱,一世牵挂,若少年时的学艺出于家人的安排,那冥冥之中的选择又注定是所有悲欢的缘起。仓央嘉措有诗曰:“谁,扶我之肩,驱我一世沉寂。”微弱的视力可能会分割两个世界,鼓词的吟唱却是一个生命生动的述说,那词那曲业已成为黄先生相携一生的伴侣。或许还是仓央嘉措诗可以帮助我们理解一个坚守的灵魂,“那一刻,我升起风马,不为祈福,只为守候你的到来。”就这样,他不曾离开过,一守护就守护了七十多年。经过考证,丽水鼓词在清朝的时候已十分盛行。作为一项古老的艺术文化,丽水鼓词在现代社会的背景下正在逐渐淡去,被人们渐渐遗忘。近年来,鼓词从业者日渐减少,老艺人逐渐过世,而新的接班人又日渐减少。让人很是担忧它的未来。但是黄景农先生用他一生的守护和吟唱告诉世人,虽然现在丽水鼓词正走向边缘,但是它的传承一直在继续。虽然它不再如当初那般盛行,他还是会继续守护,一直吟唱。

黄景农先生因创作而获得的荣誉

丽水鼓词是需要被守护的。它本身所体现的人文、社会及文化价值使得它在历史的洪流中不断前进。它的曲艺通俗易懂,音韵自然和谐,说唱生动优美。鼓词中所阐述的,是鼓词艺人们长期经历的一种缩影。在黄景农先生的创作唱词当中,我看到的有对苦难的反抗,有对生活的哲思,有社会的变迁,有历史的前进。黄景农先生的眼睛看不清,所以所有的一切他都用心去感受,用心去记录。他一生所吟唱的坚定、守候、苦难、幸福和人生便是这样在跳跃的音符中,融入鼓词里,流淌进世人的心田里,回荡在这片孕育着古老艺术的土地上,久久不息。

A Lifetime of Singing

Just with a drum blowing and hitting, a child began his lifetime of singing Guci with an infinite rhythmic beating of the drum. Huang Jingnong has been singing Guci for nearly eighty years. No matter how rough the road has been, his life-long pursuit of the art never changed. Once the career of singing Guci started, it would never end.

We sought a trace of Guci in the drizzle one day in early July and looked for the representative inheritor of intangible cultural heritage at the provincial level: Huang Jingnong. When the door opened, I couldn't restrain my excitement. When I received warm greetings from Mr. Huang and his wife and saw their smiling faces, I felt what we had done was worth doing, these several weeks of attempting to find and get in contact with him.

Mr. Huang's house was very clean and warm. When we entered the house, Mr. Huang was sitting at the table in the dining room. His wife, who opened the door for us, went to the living room and stood behind the sofa, saying something. The interpreter (due to the language barrier between us and our inheritor, I located a local high school student who could speak local dialect to accompany us to interview the inheritor) told us that she was inviting us to sit on the sofa. Although I couldn't understand what she was saying, I understood from her body language and her sincere smile that we were welcomed.

Drizzle washed away the glitz and noise of this city. Since I was going to accept the baptism of the ancient art of Guci, I couldn't help getting a bit nervous and excited. In fact, I was worried about the communication between Mr. Huang and our team members before I came here because of the local dialect. However, observing this kind couple, I suddenly remembered when the interpreter phoned Mr. Huang to make an appointment, how he replied:“Okay! Okay! I will remember the appointment and won't go out that day.” What a lovely and kind old man! I thought that I had nothing to worry about.

Stepping into the living room, I saw that on both sides of the wall hung a number of photos and certificates of honor. I asked with curiosity about the stories of those photos. At that moment, Mr. Huang was walking slowly to sofa with the help of his wife and a stick. Mr. Huang is eighty-five years old and has something wrong with his legs, so walking is very difficult for him. However, on hearing my inquiries, he did not even sit down but started to tell us the stories of the photos. Each story was inseparable from Guci. From these stories, I realized the deep love for Guci that comes from his soul. Guci is in his heart, part of his life, or his whole life, while for others it is only a kind of culture.

After every one of our team was seated, we listened to Mr. Huang recalling the past. The formal interview started as if we were sitting on a time machine. Mr. Huang's hearing was not good. During the entire interview, he kept tilting his head on one side to listen to us with attention. It seemed that the old gentleman was not good at talking because he didn't have much to say at the beginning of the interview. However, when it came to Guci, he became refreshed, clutching the seat handle, trying to straighten his back, and leaning a little forward in his seat. During the talk, he stood up and went to the other room several times to fetch us some materials that had more detailed information of what we asked for.

I was surprised to see so many honorary certificates and manuscripts among a pile of books with more relevant materials. These manuscripts were works about Guci that Mr. Huang himself had created. Some manuscripts were printed, and some were handwritten. There was the old man's name and the time of the creation of each manuscript. The latest work was created this year, and there were many honorary certificates for creative work. You could imagine how much this eighty-five-year-old artist loves Guci that has accompanied him for seventy-four years. Since Guci has been integrated into the old man's blood and become an inalienable part of his life, no difficulties could prevent him singing, let alone his old age.

Mr. Huang has sung Guci his whole life. If learning Guci was an arrangement made by his family in his childhood, his late persistence is doomed to be the source of sadness and happiness. Tsangyang Gyatso once wrote a poem:“Who, upon my shoulder, drives me through life silently?” Weak eyesight may have weakened his achievements, but the singing Guci is a vivid explanation for a complete life. It has become Mr. Hung's lifetime partner. Tsangyang Gyatso's poems can help us understand this firm soul:“At that moment / I raise the flags / not for blessing / just for waiting for your coming.” Like a guardian, he never leaves and has protected Guci for more than seventy years. Lishui Guci was very popular since the Qing Dynasty. As an ancient art, it has gradually been forgotten by people in modern society. In recent years, the number of Guci artists is declining. The old Guci artists are gradually passing away, and it is difficult to cultivate talented successors. Guci's situation is worrying. But as a guardian, Mr. Huang tells the world with his lifetime of singing that although now Guci is falling into a decline, its inheritance has been going all the time. Although it's no longer prevailing as before, he will continue his singing of Guci to protect it.

Lishui Guci needs to be guarded. It reflects the human, social, and cultural values. What it embodies drives it forward in history. Its tunes are easy to understand; its rhyme is natural and harmonious; its songs are vivid and beautiful. What it illustrates is the long-term experience of Guci artists in miniature. Among Mr. Huang's creations, there were struggles with misery and reflections on life. It also contains the changes of society and the advance of history. Mr. Huang's eyes cannot see the world clearly, so he records it with his heart and feels it with his soul. He sings about determination, expectation, suffering and happiness in life. All of these turn into the jumping notes, melting into Guci, flowing into the hearts of people and the world and echoing over the ancient land forever.